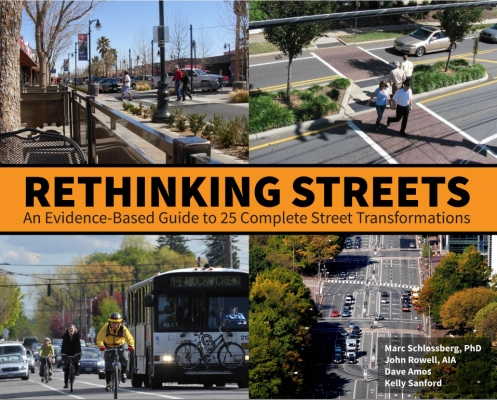

NITC researchers release Complete Streets design guide

Posted on October 19, 2014

NITC researchers have created a design manual to aid traffic engineers, transportation planners, elected officials, businesses and community stakeholders in re-envisioning their streets.

Traditionally, road design in the U.S. has been based on the simple principle of moving as many cars as possible.

The Complete Streets movement, a new way of approaching street design, is gaining ground as planners and engineers work to build road networks that are safer, more livable and can accomodate all modes of transportation.

The philosophy behind Complete Streets is that a street, in addition to being a means of reaching destinations, is also a "place" in its own right and should feel comfortable and welcoming for pedestrians and bicyclists.

To inform and encourage Complete Street redesigns, principal investigator Marc Schlossberg and co-investigator John Rowell, of the University of Oregon, put together an evidence-based design guide featuring 25 Complete Streets from around the country.

Complete Streets policies are being adopted all across the United States, but local officials have few documented guidebooks to help them think about how to retrofit streets based on best practices. This project’s aim was to fill this gap, making it easier for communities to use the evidence from other communities when making decisions about retrofitting their streets.

If you'd like the full-color manual, you can request a copy here.

Along with photographs documenting the context and before-and-after appearance of the redesigned streets, the manual provides data about collisions, economic factors, annual average daily traffic (AADT) and mode choices.

The Complete Streets movement emphasizes placemaking and a sense of shared public space. There is no single strategy; rather, designers can implement multiple strategies based on a street’s context and a project’s goals.

Many Complete Street transformations include a “road diet,” in which a four-lane road with no median or bike lanes is turned into a two-lane road (one lane in each direction), a center turn median, and two bike lanes.

Removing two automobile travel lanes may seem like it would reduce automobile throughput, but the increased flow achieved with left-turning vehicles using the center median can actually maintain or improve upon previous throughput numbers.

Other strategies often include the addition of bicycle lanes and the enrichment of pedestrian infrastructure. Additional streetscape elements like street furniture, trees and parked cars effectively slow down traffic and make the street a more pleasant place.

Some highlights from the guide:

Cycling

Cycling increased 325 percent on South Carrollton Avenue in New Orleans after the city rebuilt the road (damaged and flooded by Hurricane Katrina) and added a bicycle lane.

Safety

Pedestrian collisions at crossings were reduced 80 percent thanks to improved crosswalks at Stone Way N. in Seattle, Washington. On Nebraska Avenue in Tampa, Florida, crashed dropped by 68 percent and bicyclists reported feeling safer on the street.

Placemaking

East Boulevard in Charlotte, North Carolina now supports a cafe culture: residents and business owners wanted more outdoor dining options, and a greater separation between sidewalks and cars reduced traffic noises and facilitated al fresco dining.

Retail

Shoreline, Washington saw commerce improve along its redesigned Aurora Avenue: the city kept track of sales receipts along the corridor during the two years of construction and found a 2.9 percent dip in sales the first year followed by a 9.1 percent increase the second year.

When selecting sites for the manual, Schlossberg and Rowell consulted with the directors of the National Complete Streets Coalition, the League of American Bicyclists and the Association of Pedestrian and Bicycle Professionals, who offered guidance as to what content they thought would be most useful to their national constituencies of transportation professionals.

In addition, the research team engaged engineers and designers from local and state government and the private sector who had been involved with similar street retrofit projects.

The NITC researchers chose to focus on fairly typical streets. There have been notable projects around the country where very substantial street changes have taken place (for example, turning Times Square into a pedestrian mall), but the focus of this project was to find examples that many communities of different sizes, locations, and political tendencies could learn from.

For more information, visit the project page.