The Importance of Transportation to Refugees in Tucson, Arizona

In 2022, one in ninety-five people in the world were forcibly uprooted from their homes, causing them to seek homes in other countries—that is, become refugees. Resettlement in a new country allows them to escape unpredictable or unsafe conditions, but it comes with its own array of challenges. Though refugees’ satisfaction in their post-resettlement environments has been studied, the role of mobility in their qualities of life remains understudied.

To fill this research gap, professors from the University of Arizona conducted a mixed-methods study with members of the refugee community Tucson, Arizona. Their goal was to understand how transportation impacts refugees’ well-being in order to develop recommendations for how cities and nonprofits can better serve this vulnerable portion of the population. The findings not only highlighted the importance of transportation to refugees and the number of barriers that prevent refugees from fully utilizing the systems in place, but also provided interesting insights into perspectives of transportation that challenge the traditional white feminist viewpoint of gender roles. They challenge the idea that the population of refugees can be generalized, and they place an emphasis on the importance of individual experiences.

To learn more about the findings, watch an October 2023 webinar.

An impressive academic review established that the ability to get to places of importance is critical to Tucson refugees for leading fulfilling post-resettlement lives. It also showed that transportation-related stressors negatively affect refugees’ mental health. This may be unsurprising when the long list of barriers to refugees’ access to transportation is revealed:

- Discrimination and prejudice from transportation providers and other community members

- Inadequate public transportation infrastructure and services to refugee neighborhoods

- Language barriers limiting access to information, including transportation schedules and maps

The researchers collected data with a survey and interviews. Sixty-two refugees living in Tucson were contacted through refugee and social work services and completed the survey. An additional thirty-five were interviewed. Interviewees came from thirteen different countries, including the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, and Iraq.

Along with demographics, the survey asked questions regarding refugees’ transportation and mobility habits. Respondents gave information such as their primary modes of transportation, reasons for not using public transportation, and how often they are negatively impacted by mobility-related challenges and what feelings they experience. The survey revealed that most refugees rely on the public bus system initially upon arrival to town, but personal vehicles were the primary mode of transportation among respondents. Reasons for not using public transport included a lack of accessibility, inadequate service, and a lack of understanding, just to name a few. Ninety-five percent of survey respondents reported that their well-being was impacted by transportation and mobility-related challenges with the primary experienced feeling being anger.

The results of the interviews support the findings of the survey while providing a more nuanced, personalized perspective. Notably, a young woman named Constance (whose family is from Congo) shared that from her perspective, her dad choosing to take on the role of the driver for the family was a selfless risk rather than a strategy of oppression. Regarding her dad’s choice, Constance said, “He did not do it in a way that was like ‘only I have to do it, you guys can’t do it’ but in a way that, ‘I will do it first so that way I can provide a way for you guys to go next.’” This challenges the preconceived notion that a father figure who holds a position of power in a family must be oppressing the “subservient” woman or women in the family who “need to be rescued.” On the contrary, Constance now drives her own car and has an active, dynamic role in her social network; she helps give back to her community by driving new refugees where they need to go.

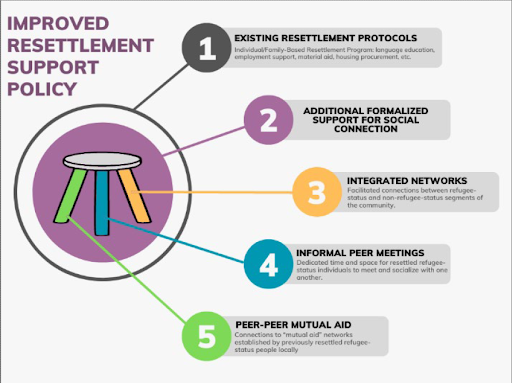

All this being said, Constance (along with the other interviewees) shared the difficulties of navigating the public transit system. Some interviewees had ideas for making the transportation system in Tucson better. They recommended more buses, more destinations for public transport, more bus departure and arrival times, and a more navigable and intuitive system. Additionally, the researchers proposed some solutions. Student assistant Sarah Clark developed a way to present these solutions: with an image of a three-legged stool.

The three legs of the stool represent suggestions that would be integrated into existing individual-centered resettlement programs (represented by the gray ring) and make establishing social bonds easier (represented by the pink circle). Notice how much emphasis is placed not only on connecting refugees and non-refugees but also on connecting refugees with each other, therefore creating their own support network like in Constance’s case. A couple of key questions to consider when building these connections are:

- Will focusing on connecting refugee-status people with people from their own regions/language/groups/cultures/etc. facilitate social segregation rather than full integration into new host communities?

- Will relying on refugee-status volunteers to spearhead mutual support unjustly overburden them?

The answer to these questions is the same: neither worries will be problems if the entirety of the three-legged stool approach is implemented. Because the approach encompasses integration into the non-refugee community, social segregation will not take place; because it is intended to supplement, not replace, support from agencies, then the volunteers will not be unjustly overburdened.

This research is valuable not only because it highlights a need in the community and offers solutions for that need, but also because it encourages readers to not generalize any one population or group of people. In a society that loves to place labels on people, it is sometimes difficult to remember that each individual’s experiences are unique, and there is no such thing as one-size-fits-all. Researched during a time of anti-refugee sentiment in the US, these findings encourage policymakers and citizens alike to examine their preconceived notions about refugees and honestly evaluate whether their opinions are helpful or harmful to the community as whole.

This research was funded by the National Institute for Transportation and Communities, with additional support from the University of Arizona.

RELATED RESEARCH

To learn more about this and other NITC research, sign up for our monthly research newsletter.

- Transportation Behavior Among Older Vietnamese Immigrants in the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex

- Toward Data and Solution-Focused Approaches to Support Homeless Populations on Public Transit

- Do Travel Costs Matter For Persons With Lower Incomes? Using Psychological and Social Equity Perspectives to Evaluate the Effects of a Low-Income Transit Fare Program on Low-Income Riders

ABOUT THE PROJECT

Photo by photoquest7/iStock

The National Institute for Transportation and Communities (NITC) is one of seven U.S. Department of Transportation national university transportation centers. NITC is a program of the Transportation Research and Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University. This PSU-led research partnership also includes the Oregon Institute of Technology, University of Arizona, University of Oregon, University of Texas at Arlington and University of Utah. We pursue our theme — improving mobility of people and goods to build strong communities — through research, education and technology transfer.