Biking Safely Through the Intersection: Guidance for Protected Bike Lanes

- This research is also featured in a May 2019 addendum to NACTO's Urban Bikeway Design Guide: Don't Give Up at the Intersection

Protected bike lanes are becoming increasingly common around the United States, yet there is little guidance for how to extend the protected lanes through one of their most dangerous links: the intersection. Led by Chris Monsere and Nathan McNeil of Portland State University in collaboration with Toole Design Group, the latest report from the National Institute of Transportation and Communities (NITC) offers contextual guidance for designing intersections that are comfortable for cyclists.

WHY FOCUS ON INTERSECTIONS?

Safety and perceived comfort are the two key considerations for cities attempting to build connected low-stress networks, given the positive correlation between perceived comfort and ridership. Studies, including our Lessons from the Green Lanes: Evaluating Protected Bike Lanes in the U.S., have consistently found that people prefer bike facilities that are separated from traffic, such as off-street paths and protected bike lanes, with physical separation such as a post or concrete curb.

The preference for these separated facilities appears to be greatest amongst cyclists who ride primarily for recreation (as opposed to transportation), those who cycle less, as well as the subset of potential bicyclists who self-identify as "interested but concerned." Research suggests that providing comfortable designs may be vital to expanding the bicycling population beyond current riders.

However, studies of bicyclists’ sense of safety and comfort have generally focused on road segments, rather than the intersections of those roads. Using video microsimulations to estimate expected bicyclist and turning-vehicle interactions, researchers paired those results with in-person surveys to establish bicyclist comfort based on intersection design type and volumes.

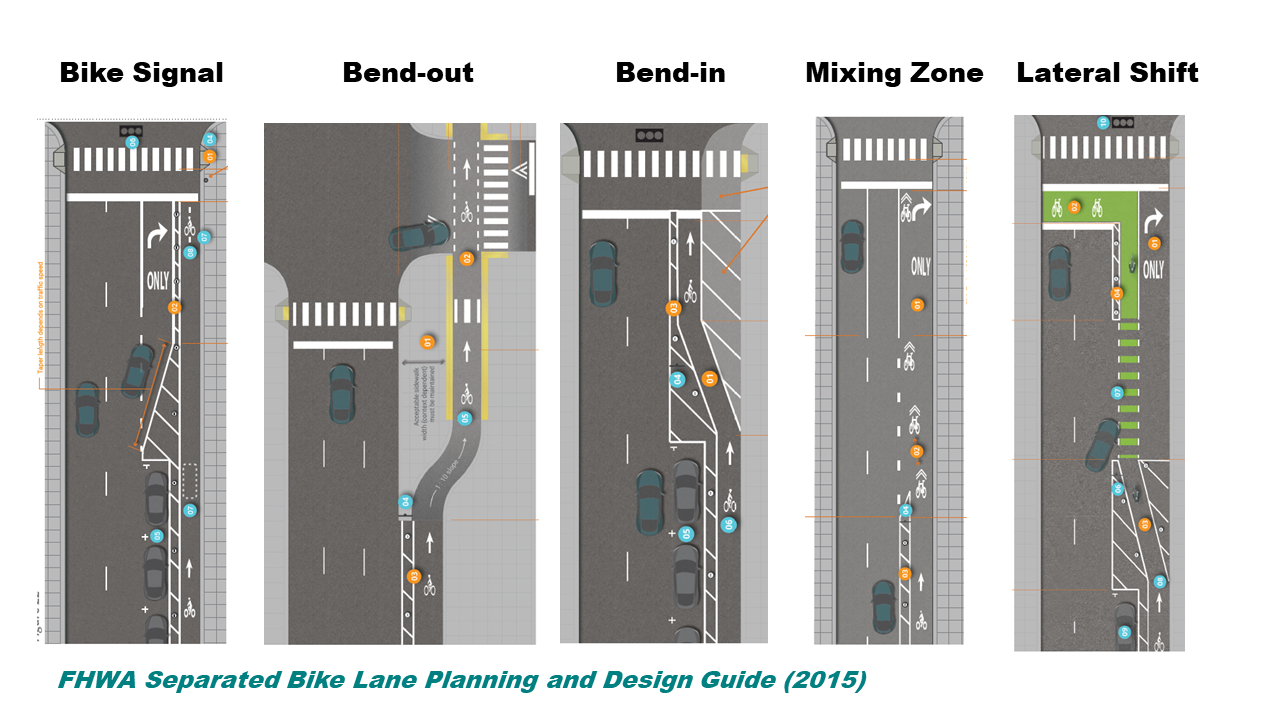

TYPES OF INTERSECTION DESIGNS

This research did not explore actual safety in terms of crash data; we intentionally focused on the comfort question first. We limited the scope to one-way configurations and focused on the right-turning interaction between bicycles and vehicles. This interaction seems to drive many design decisions, since that is where the most movement is.

Separated Bike Signal Phase: A signalized intersection wherein motor vehicle traffic and bicycle traffic have separate traffic signals that separate out their movements in time.

Bend-In: This approach shifts the bike lane in toward the motor vehicle lanes, which can increase visibility and awareness of bicyclists and motorists of one another.

Bend-Out: Shift the bike lane away from the motor vehicle traffic, which results in turning motorists having exited the through travel lane prior to crossing the bike lane, slowing their speed and approaching the crossing at closer to a 90 degree angle. The design commonly known as a "protected intersection" is a type of bend-out design.

No-Bend/Straight Path: (Not pictured) Keep the bike lane separated right up to the intersection. There is no bend but there is an offset distance from the vehicle lane. For an example, see video at the 18 minute mark.

Lateral Shift: Move the bicyclist out and provide a crossing area for turning-motorists to shift into a turn lane, with their paths crossing before the bike lane is reestablished to the inside of the turn lane.

Mixing Zone: Establish a right turn lane and end the bike lane, creating a mixing area for bicyclists and turning motorists.

KEY TAKEAWAYS FOR PLANNERS AND ENGINEERS

The final report summarizes guidance for two broad types of cyclists; interested but concerned and bike-inclined (which encompasses both "Enthused and Confident" and "Strong and Fearless" in the classic typology). The first step is for a city to select the cyclist type they are trying to attract. Importantly, comfort scores for the "Interested but Concerned" groups suggest only the separated bike signal phase and "protected intersection" (aka bend-out) as recommended designs.

One of the key drivers of comfort, according to the results from surveys and focus groups, is minimizing the distance/time that cyclists are mixing with traffic. Key findings:

Most Comfortable: Protected intersections (aka bend-out) and separated bike signal phases were found to provide the most comfort to the most people.

Moderately Comfortable: Designs that keep a separate bike lane (bend-in, straight-path) were rated as comfortable by more than half of all respondents, but were sensitive to the presence of turning vehicles. It may be that without the vehicles in the video clip, the design implies separation from vehicles and is rated higher but when shown interacting with vehicles, it is more apparent to the extent cyclists must mix with traffic.

Least Comfortable: Designs that move bicyclists and motor vehicles into shared space (mixing zones or lateral shifts) were viewed as least comfortable. There was not a difference in the comfort of mixing zone designs with or without vehicle interactions. One potential reason for this is that mixing zones cyclists and motor vehicles are already primed for interaction (as opposed to separated spaces). Additionally, in most of the cases in which cyclists were negotiating interactions with turning vehicles, the vehicles were moving quite slowly.

Exposure distance is a significant predictor of comfort. It’s measured as the end of vertical separation on one side of the intersection to the start of separation on the far side.

Conflicts in bend-out intersections may have the lowest severity of conflicts. With the same bicycle and right-turning vehicle volume, the number of conflicts in bend out or protected intersections was the highest and the number of conflicts in bend-in intersections was the lowest. However, the average maximum speed of a vehicle involved in a conflict was lowest in bend-out (or protected) intersections.

WHO WAS SURVEYED?

The research approach was guided by the assumption that cyclist comfort is a key desired design outcome. In-person video surveys were used to identify people’s comfort levels while bicycling through a variety of intersection designs under defined conditions (e.g., with or without interactions with turning motorists). See an example of the type of clip that was played for the participants. Video data and microsimulation models were used to inform the comparison of the design options and analyze anticipated interactions at various bicycle and vehicle volumes for each of the design options.

A total of 277 respondents rated 26 video clips showing cyclists riding through a variety of intersections, for a total of 7,166 ratings. Surveys were conducted at four locations in three states, including urban and suburban locations in Oregon, Minnesota and Maryland.

The survey respondents represent a mix of current travel behaviors and bicycling experience, including some people who don’t ride at all (particularly for transportation purposes), some who have not ridden in the past year, and some who ride regularly.

Women and non-white respondents were generally less likely to feel comfortable than other respondents.

Those who indicated that they rode for transportation in the past year had higher average comfort ratings than those who did not.

THE RESEARCH TEAM

Portland State University

Toole Design Group

This research was funded by a pooled fund grant from the National Institute for Transportation and Communities (NITC), with additional support from Portland State University, Toole Design Group, the Portland Bureau of Transportation, the City of Cambridge, Massachusetts, SRAM Cycling Fund, and TriMet. Learn more about NITC's pooled fund program.

RELATED RESEARCH

To learn more about this and other TREC research, sign up for our monthly research newsletter.

- Lessons from the Green Lanes: Evaluating Protected Bike Lanes in the U.S.

- Operational Guidance for Bicycle-Specific Traffic Signals

- Improved Safety and Efficiency of Protected/Permitted Right Turns in Oregon

The Transportation Research and Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University is home to the National Institute for Transportation and Communities (NITC), the Initiative for Bicycle and Pedestrian Innovation (IBPI), and other transportation programs. TREC produces research and tools for transportation decision makers, develops K-12 curriculum to expand the diversity and capacity of the workforce, and engages students and professionals through education.