Transit Impacts on Jobs, People and Real Estate: Real Estate Rents

The latest report funded by the National Institute for Transportation and Communities – Transit Impacts on Jobs, People and Real Estate, from the University of Arizona – represents the culmination of nearly a decade of research into the economic effects of transit. To unpack the dense and substantial findings from 17 LRT, 14 BRT, 9 SCT, and 12 CRT systems in 35 metro areas across the United States, we've been telling the story in chapters. Last month we focused on how transit affects where people live, and before that we explored how it impacts the locations of jobs.

This month, we're delving into volume 4 of the final report: Impact on Real Estate Rents with Respect to Transit Station Proximity Considering Type of Real Estate by Transit Mode and Place with Implications for Transit and Land Use Planning (PDF).

WHAT DO REAL ESTATE RENTS TELL US ABOUT TRANSIT?

"Real estate markets can tell transit and land use planners much about the effectiveness of transit stations in influencing real estate development around them," said Arthur C. Nelson, the lead researcher on the project.

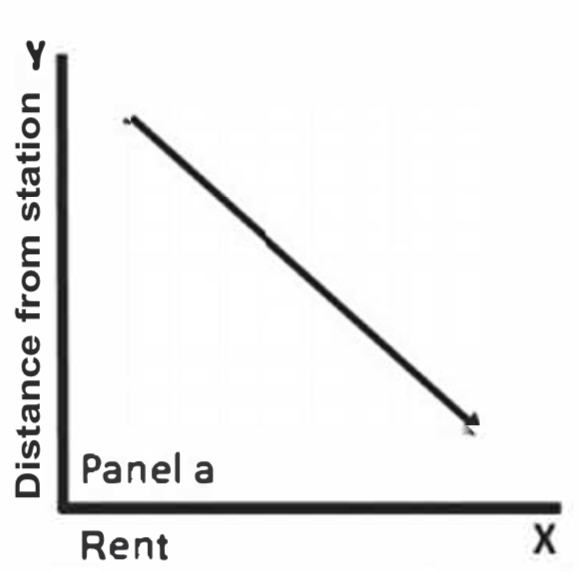

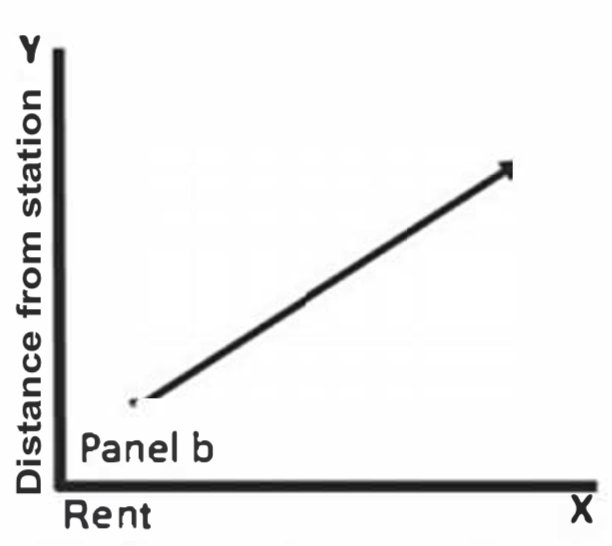

For example, if office, apartment and retail rents go up the farther away they are from transit stations, the market is signaling that those stations are not attractive places around which to locate; this is a negative market signal. If, on the other hand, rents fall as they get farther away from transit stations, this is a positive signal; it means investors and tenants are willing to pay more for locations near the station.

The research reported in this volume is the most comprehensive assessment of market responsiveness to transit station proximity ever published. It applies the same modeling and database used in the previous volumes to real estate rents for more than half a million office, multifamily and retail properties and more than 50 transit systems, operating in more than 30 metropolitan areas. Four major transit modes were studied: light rail, streetcars, bus rapid transit and commuter rail.

"Results are mixed but the bottom line is that the real estate market is telling transit and land use planners what needs to be done to make station locations, designs, and land use planning around them more effective in attracting real estate investment," Nelson said.

QUANTIFYING TRANSIT IMPACTS ON THE REAL ESTATE MARKET

Living, working and shopping around transit stations offers the ease of car-free travel by public transportation, and rents are affected by this amenity benefit of transit station proximity. However, this benefit can be offset by externalities such as noise, traffic, and simply the unattractiveness of stations and station areas. To reflect the push and pull of amenities and externalities, the researchers identified four theoretical outcomes of transit station proximity on real estate rents.

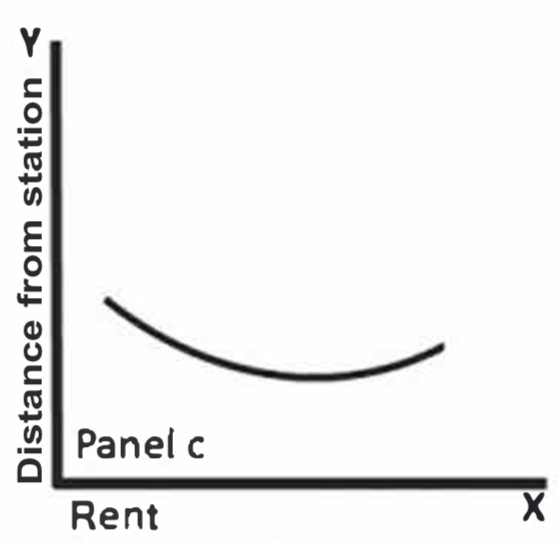

To put it simply, transit station area rent slopes consistent with panels A and C would seem to advance transit objectives, while rent slopes consistent with panels B and D would not.

Panel A: Rent falls as distance from a transit station increases, signaling proximity is an amenity. | Panel B: Rent rises as distance from a station increases, signaling proximity is an externality. |

Panel C: A convex relationship where amenity effects prevail at some point before externality effects do. | Panel D: A concave relationship where externality effects prevail at some point before amenity effects do. |

CITIES THAT ADVANCE TRANSIT OBJECTIVES

The research sought to answer two questions: Is there an association between commercial real estate rent and proximity to fixed route transit stations? If so, what is the form of that relationship?

Researchers used a temporal, cross-section quasi-experimental research design. Examining office rents from 2019, and multifamily and retail rents from 2018, the team tested for the association between transit station proximity on real estate rents per square foot. Though not causal, the associations can be used as guidance for transit and land use planning nonetheless. For the most part, they found that transit station areas do not advance transit station area purposes with respect to attracting real estate investment, because rents are mostly upward/concave, sloping away from transit stations or ambiguous.

However, researchers did identify individual systems with downward/convex sloping rent gradients that are worthy of case study analysis to draw lessons for other systems to emulate. They selected metropolitan areas with positive associations between rent and transit stations to serve as "exemplars" for advancing transit objectives. If case study analyses are done on the selected sites, planners and urban designers could learn important lessons about station design, transit and land use planning, and urban design from the station outward.

Exemplar Cities Based On Office Rents

Exemplar Cities Based On Multifamily Rents

Exemplar Cities Based On Retail Rents

GENERAL TRENDS AND PATTERNS

The relationships between rents and transit systems are complex and vary greatly. The final report offers a wealth of detail and analysis for each type of real estate and each type of transit system, and anyone curious to learn specifics should download the full fourth volume: Impact on Real Estate Rents with Respect to Transit Station Proximity Considering Type of Real Estate by Transit Mode and Place with Implications for Transit and Land Use Planning (PDF). However, a few general trends can be seen.

- Overall, the analysis suggests that multifamily and retail land uses may push office real estate away from light rail transit stations, to about 0.50-mile. But as we see for individual metropolitan areas, this trend is not evident everywhere.

- Similarly, multifamily and retail real estate may be outbidding office real estate at or near streetcar stations, pushing offices further away. With streetcars gaining popularity around the US, the researchers recommend in-depth case studies of all six “exemplar” cities identified.

- In general, real estate rents do not respond well to bus rapid transit station proximity. Researchers found ambiguous office and multifamily market responses to BRT proximity. Retail rents were higher in the second distance band, about 0.25 miles from the station, and lower in the first and third – i.e. rents went down both closer to the station, and farther away from that 0.25 mile sweet spot. Researchers surmise that for the most part, BRT stations are sources of externalities. They expect that improved transit and land use planning and better urban design can overcome these externalities, making BRT stations sources of amenity value.

- Commuter rail transit stations had positive impacts on office and retail rents, but only flat or ambiguous impacts on multifamily rents. While CRT stations can be sources of externalities such as noise, smells, unappealing freight-based rail infrastructure and so forth, perhaps with sensitive transit and land use planning, and especially urban design, these potential nodes of externalities could be turned into places of amenities for multifamily development as well – or at least places where the amenity benefits exceed externality effects.

IMPLICATIONS FOR TRANSIT AND LAND USE PLANNING

Transit systems do a lot of things. Primarily they move people from Point A to Point B, but they are also used to achieve social justice and other goals—for example, connecting lower income neighborhoods to regional job opportunities; renewing historically disinvested areas to create jobs and connect them to their regions; reducing congestion on roads, thereby providing public health benefits; and even elevating the public relations prestige of local and regional governments.

But there can be downsides as well. Transit stations can become localized sources of disinvestment if the real estate market—both investors and consumers—are unwilling to invest at or near them. They can also contribute to displacement of lower-income households through gentrification.

But how do we really know the effects of transit stations on people and the economy? Without meaning to overstate it, the real estate market may be the single best indicator of whether transit stations are having desirable or undesirable effects. Transportation professionals can use the market to gauge the extent to which transit and land use planning, and urban design interventions achieve desirable outcomes. Learning how to interpret the lessons of real estate markets can help cities achieve their economic, equity, sustainability-related goals as well as other desired outcomes.

ABOUT THE PROJECT

- Download the Full Final Report (All 5 volumes in one PDF)

- Download the page Project Briefs:

- Volume 2 (PDF)

- Volume 3 (PDF)

- Volume 4 (PDF)

- Volume 5 (coming soon - August)

- Watch the recorded webinar from March 23, 2021

The final report is presented in five volumes, with the first volume serving as an orientation and introduction:

- Volume 1: Orientation, Executive Summary, Context and Place Typologies (PDF)

- Volume 2: Impact on Job Location Over Time with Respect to Transit Station Proximity Considering Economic Groups by Transit Mode and Place Typology with Implications for Transit and Land Use Planning (PDF)

- Volume 3: Impact on Where People Live Over Time with Respect to Transit Station Proximity Considering Race/Ethnicity and Household Type and Household Budget by Transit Mode and Place Typology with Implications for Transit and Land Use Planning (PDF)

- Volume 4: Impact on Real Estate Rents with Respect to Transit Station Proximity Considering Type of Real Estate by Transit Mode and Place with Implications for Transit and Land Use Planning (PDF)

- Volume 5: Improving Transit Impacts by Reconsidering Design and Broadening Investment Resources (PDF)

This research was funded by the National Institute for Transportation and Communities, with additional support from the University of Arizona, Tucson.

As principal investigator, Dr. Arthur C. Nelson’s research on this topic spans many years:

- (2012) Do TODs Make a Difference?

- (2013) National Study of BRT Development Outcomes

- (2019) Updating and Expanding LRT/BRT/SCT/CRT Data and Analysis

- (2019) Nationwide Worker Data Repository to Analyze Transit Outcomes - explore links between transit station proximity and real estate rents, jobs, people, and housing

To learn more about this and other NITC research, sign up for our monthly research newsletter.

Photo by csfotoimages/iStock

The National Institute for Transportation and Communities (NITC) is one of seven U.S. Department of Transportation national university transportation centers. NITC is a program of the Transportation Research and Education Center (TREC) at Portland State University. This PSU-led research partnership also includes the Oregon Institute of Technology, University of Arizona, University of Oregon, University of Texas at Arlington and University of Utah. We pursue our theme — improving mobility of people and goods to build strong communities — through research, education and technology transfer.